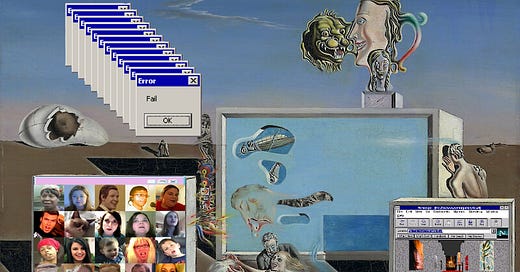

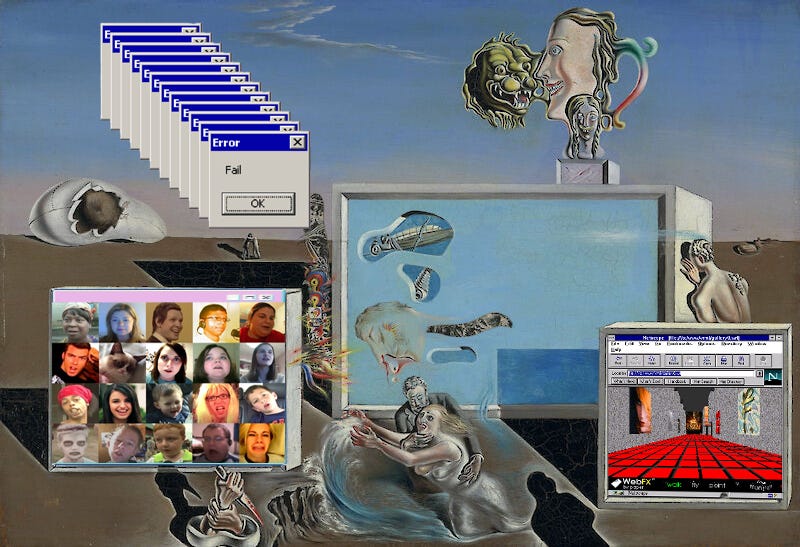

Does anything go truly viral these days? I scroll and I scroll, looking for the next bit of high-fructose algorithmic crack to get excited about. I regularly watch videos that have racked up millions of views. Surely a video with 30 million views should be considered viral right? Many people have been observing that the most “viral” videos on TikTok are ones that you’ve likely never seen. Take for example the most successful TikTok of 2023. I bet you’ve never seen it. I have never even heard of this person, and my daily average screen time for my iPhone alone hovers around 7 hours a day (that doesn’t include the time I spend on my laptop). This is the state of the internet now. Our idea of “viral,” hasn’t existed in its truest form since the early, primordial days of the web, before we were goaded deeper and deeper into our algorithmic holes.

Previously, you were forced to consume centralized media. Everyone engaged with the same bits of culture, news, ideas, and fashions. A few players and institutions controlled the means of distribution. Think about the power Anna Wintour once commanded over fashion; her ability to steer how the world dressed and looked is practically unparalleled and will likely never be matched. She was a kingmaker for designers, photographers, stylists, and anyone who existed in the creative space, the same way Rupert Murdoch or Ted Turner could once upon a time crown the Republican and Democratic nominees. “Politics is what comes out the asshole. Wouldn’t you rather be upfront, feeding the horse?” As Logan Roy once aptly said.

“The flight to social media flattened the distinction between legacy brand—Vogue, Random House, MTV, Hot 97, MoMA, even The New York Times—and internet personality. While this raised the individual agency for certain artists/writers/designers/whatever, it diminished the power of cultural institutions… The free-wheeling early days of social media seduced creative scenes into believing a new decentralized paradigm had been achieved. Who needs stuffy zombie institutions when we have Instagram? The problem with non-hierarchical models is human beings are not non-hierarchical creatures. Like all anarchist ideals, the dream of infinite digital liberty turned out to be more corporate talking point than reality.”

-

, Live Players pt. 1.

Today, everyone inhabits their own digital enclave – your feed is a reflection of your tastes, opinions, and thoughts. Moreover, it is carefully manipulated, maintained, and manicured by tech oligarchs sitting in control of the algorithms that control the flow of information. The videos, memes, and trends that become popular these days are driven by opaque algorithms trying to hook users to the app. It’s all based on every aspiring zuckerfuck’s favorite KPI that they can sell to advertisers: time spent on app. 50 years ago people looked to major journalistic outlets for news and large magazines for cultural enrichment, where it was all gathered with a humanistic and curatorial approach. The politicians, stories, music, movies, artists, and designers that became popular were ideally picked by people with nuanced tastes. (And along with the power to select winners came great corruption). These days, smarter people with great taste will consequently curate a better feed that presents them with good or better information from more reliable sources. We’re post-viral, constantly inundated with content and surfing a complex fragmented web of information that most people can’t make sense of – burdened by infinite choice. The logical next step is a return to gatekeeping, influential IRL creative scenes/subcultures, and a restructuring of institutions.

For people without taste or, frankly, time, curating information is a hard thing to do. People need elite tastemakers to guide them and organize information in a place that serves as a singular, highly trusted source of truth or inspiration. Who will be the next Anna Wintour? The next New York Times? The next Harvard? The next NIH? We trusted a few different media institutions to have a monopoly on truth and they’ve failed us time and time again – public trust is at an all-time low. We trusted virologists to predict the next pandemic and they ended up creating a new one, stuck in a hamster wheel of grant proposals doing riskier and riskier research with little to no upside. Slowly but surely, institutions with iron-clad reputations have lost their prestige, their blatant incompetence and corruption has created a crisis of faith. All of this was only possible due to the rapidly changing nature of information and media – like the Catholic Church’s slow demise at the hands of the printing press, so too will our current structures be replaced by something stronger and better. However, as these once-iconic taste-making institutions disintegrate, we are at the mercy of social media algorithms which have decentralized and fragmented the internet, and on a larger scale, our culture. Culture is stuck.

“We’re addicted to 19th-century myths. We presume the present is more alive than the past…. Change still comes but it feels more like a hack, a remix, a mash-up— which in and of itself feels like a return to the eclecticism of the early 21st century hipster.”

-

, Live Players pt. 2.

Culture is stuck because as Paul Skalas noted, “Culture is no longer made. It is simply curated from existing culture, refined, and regurgitated back at us. The algorithms cut off the possibility of new discovery.” The reason we saw major shifts in fashion, music, ideas, and aesthetics in the ’50s, ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s, etc.. is because we had top-down direction from large cultural tastemakers in radio, TV, Hollywood, and fashion houses.

“The dream of infinite digital liberty” as Sean Monahan pointed out, was simply a force of competition that exposed the deep systemic rot endemic to pre-internet media consumption: why should I be forced to buy a cable subscription when I can watch YouTube? On the flip side, why is my only chance at success guaranteed by a major network when I can post content on YouTube for free and amass an audience? Why should 1 or 2 media conglomerates have the power to crown the president of the United States? Why should a few people get to determine what’s true and what isn’t true? But like most communications-based innovations, we benefitted at the individual level at the expense of the collective.

In the post-viral world, the level of curation needed to produce a steady and healthy media diet requires a lot of the right variables inputted; it means having the ability to know which people to follow. Knowing when certain information is good and when it’s bad, and most of all, having the ability to not constantly fall into a cycle of confirmation bias. This can be applied to a multitude of sectors; the tendency for fashion trends to have a global impact via TikTok is slowly decreasing, drowned out by algorithmic sorting. Just because a trend goes viral for you, doesn’t mean it went viral for me. Furthermore, something that gets a ton of views or engagement doesn’t mean it’s cool. You can’t quantify coolness or good taste. The more influential hipster types will be tapped into real communities that are on the cutting edge of creativity and self-expression. The flattening of the trend curve and the erasure of geographic or sub-cultural specific trends is going to slowly reverse course. Creative scenes like Dimes Square will become much more prominent. Subcultures will coalesce around like-minded people IRL, and the real cultural curation will happen outside of the internet. People aren’t able to pick up on trends as quickly as they were, say, a few years ago, because our understanding of “virality” is changing by the minute. The real trends are being created in spaces that people physically aren’t in or aren’t allowed in. In that sense, the elite tastemakers, those part of the next burgeoning creative scenes, will have a better understanding of the truth and play a much larger role in influencing culture and the institutions that make sense of culture. Gatekeeping will make a triumphant return. When and who will rise to the occasion?

I had never considered our post-viral era before. Upon recalling the innocent joy of watching the Oogachaka Baby dance compared to the perplexity I constantly experience when witnessing current TikTok trends, I find myself in agreement with this perspective. Yet, I imagine many still hold the belief that going viral is possible, given its technical feasibility. There is probably a term for this phenomenon, representing the gap between the desire to go viral and the unlikelihood of it happening.

Regarding the premise that "culture is stuck," I'd like to offer a contrarian view: culture has already been liberated. I believe the opportunity space is so vast right now for individuals to experiment both philosophically and artistically, scenemaking toward the creation of radically different cultures. This reminds me of Arturo Escobar's concept of the pluriverse: the coexistence of multiple diverse worldviews, ontologies, and ways of knowing.

Yes, "mainstream" culture is undergoing a Disneyfication/McDonaldization process, becoming increasingly dispirited and defutured. However, I do see a pluriverse emerging alongside it. If this is true, this would be my answer to your query about elite tastemakers: those who promote the pluriverse will wield the most influence, even if they are not the ones who go viral.

this is a great diagnosis

such highly personalized algorithms replacing big cultural institutions is making society more individualistic. our algorithms are deeply personal and are likely completely alien to the next person. the result is creating more unique personal taste and style. p cool to witness it from the start